Sri Lanka president’s debt deal speech raises doubts: real relief or election rhetoric?

- President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s debt restructuring announcement seemed more like a campaign speech, analysts said

Wickremesinghe announced the conclusion of a final agreement on debt restructuring with Sri Lanka’s main bilateral creditors, including Japan and India, marking the end of debt restructuring negotiations with the Official Creditors’ Committee (OCC), during an address to the nation on Wednesday.

He also noted that a final agreement had been reached with China’s Exim Bank.

Under this week’s agreements, Sri Lanka is allowed to defer all bilateral loan instalment payments until 2028 and repay these loans on concessional terms, with an extended period until 2043. This arrangement will allow the country to maintain debt payments at less than 4.5 per cent of its GDP between 2027 and 2032. Additionally, its gross fiscal requirement, including loan repayments, is expected to decrease by more than 13 per cent by the period of 2027-2032.

These agreements are to be introduced to the Parliament to be ratified in a special session on July 2.

However, many analysts criticised Wickremesinghe’s description of the debt restructuring as politically motivated, given the presidential elections taking place in October.

Wickremesinghe has remained indecisive of holding the elections this year, despite his term coming to an end, and earlier this month his party’s general secretary suggested postponing the elections by two years through a referendum.

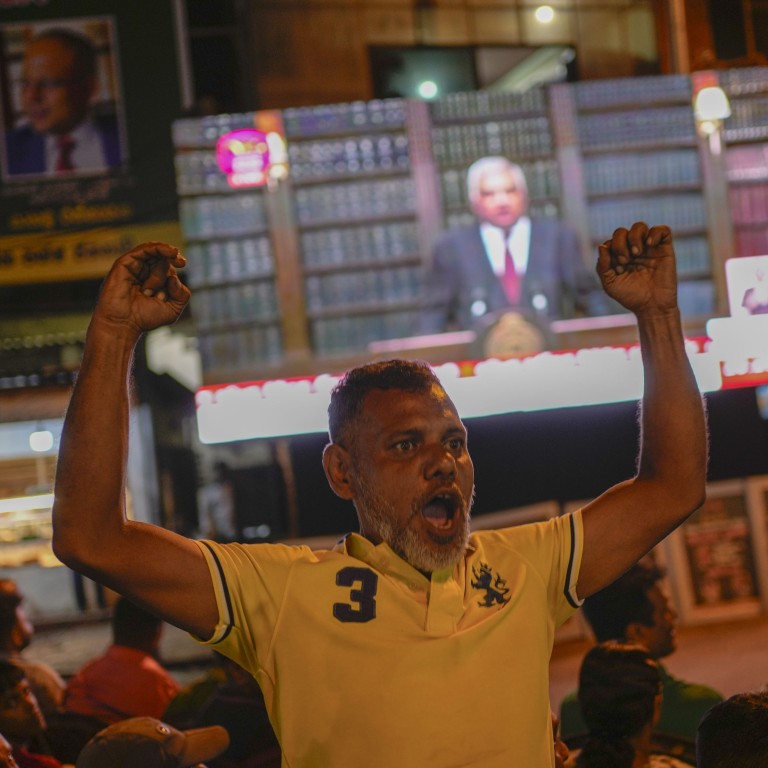

Some observers said his address to the nation sounded like a campaign speech. At one point he asked, “Will you move forward with me, who comprehended the problem from its inception, offered practical solutions, and delivered results? Or will you align with those grappling in the dark, still struggling to grasp the issues?”

Professor Nirmal Ranjith Dewasiri, a political analyst and lecturer at the University of Colombo, viewed Wickremesinghe’s speech as an attempt to secure the support of his United National Party (UNP)’s traditional constituency from his political rival and opposition leader, Sajith Premadasa.

Premada’s party, Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB), split from the UNP in 2019, and went on to secure 23.9 per cent of the vote during the general elections of 2020. Despite the split, the SJB still garners support from much of the UNP’s traditional constituency, Dewasiri said, noting that Wickremesinghe’s party suffered a historic defeat in those elections.

Wickremesinghe later rose to the presidency through a parliamentary vote following former president Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s resignation during the political unrest caused by the economic crisis of 2022. While the appointment was constitutional, many Sri Lankans call Wickremesinghe a “president without a mandate.”

Based on the results of the 2020 general elections, the UNP constituency heavily favours Premadasa and he has only consolidated his grip over them in the last few years, Dewasiri added.

“But now, Wickremesinghe has gained the upper hand since he is the incumbent and he is attempting to gain popularity with his vision for economic recovery, to succeed over Premadasa,” he said.

“It’s now like the American primaries.”

According to Dewasiri, Premadasa still remains much more attractive in rural parts of the country and, unless the UNP can make a deal among the parliamentary groups and second level leadership, it is going to be difficult for Wickremesinghe to win the election if Premadasa is also running.

That means the real question now is whether Wickremesinghe or Premadasa will challenge NPP leader Anura Kumara Dissanayake for the presidency.

“It cannot be both, if it is both, then it gives massive mileage to Dissanayake,” he argued.

Ahilan Kadirgamar, a political Economist from the University of Jaffna, said Wickremesinghe is attempting to sell the agreements on debt restructuring as some kind of recovery, or even success, out of default. But it will not work on the ground level because people are still struggling with the increased cost of living due to the severe austerity measures of the IMF programme, he said.

“Maybe it will work for the business elite in Colombo, and international actors, but it’s not going to gain much traction,” he says.

Kadirgamar argues 4.5 per cent of GDP equivalent to debt repayment is, as of now, going to be about 30 per cent of the country’s budget.

“To put it another way, we will only have about 3.3 per cent of GDP growth. In these times, that is very low for a developing country. So there is no success here,” he said.

Meanwhile, Rajni Gamage, a political science researcher at the National University of Singapore’s Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), viewed Wickremesinghe’s speech as politically divisive and designed to deflect criticism.

“Wickremesinghe’s speech is framed in such a way to show those supporting the debt restructuring agreement with official bilateral lenders as patriots. Those who opposed it were referred to as people who did not ‘genuinely care about our country’s welfare’ and have ‘betrayed the country’,” she noted.

This undermines genuine criticism of the government’s actions and the terms of the debt restructuring agreement, she said.

“Any criticism or opposition to the government is now labelled as election campaign-motivated and driven by power interests, while the president’s actions are automatically assumed to be in ‘the national interest’,” she argued.